Hi! + Kairos

Read Kairos if you love historical dramas and if you value brilliantly brutal prose.

Hey there. It's Leigh KP.

This is the very first edition of Billy, a newsletter about the books I love. I started this newsletter to feel like a creative human and to put something human on the internet. This act doesn’t make me special, but it does make me part of the resistance. There is so much media at our fingertips, media presented to us based on algorithms responding to “engagement events.” Rather than a list of recommendations tallied together for no other purpose than to serve ads, I offer recommendations of books that made me feel something. Engagement is not a feeling, and yet it seems to be the way curation is heading. We need human critics more than ever, even though tech billionaires strip our thoughts and leave us with the promise of pageviews. Zines and blogs may not save us, but we need the independent weirdos to keep writing, thinking, criticising, recommending. So here’s my part: Billy.

What you’ll find:

I don’t care much about newness. Reviewing “this week’s read” is someone else’s job. I read on whims and highlight books that make me feel.

I listen to lots of podcasts too, so you’ll see some podcast episode recommendations.

For now, Billy is monthly, but I’ll post short musings and pretty things on Instagram. Follow me @billybooknews

This month:

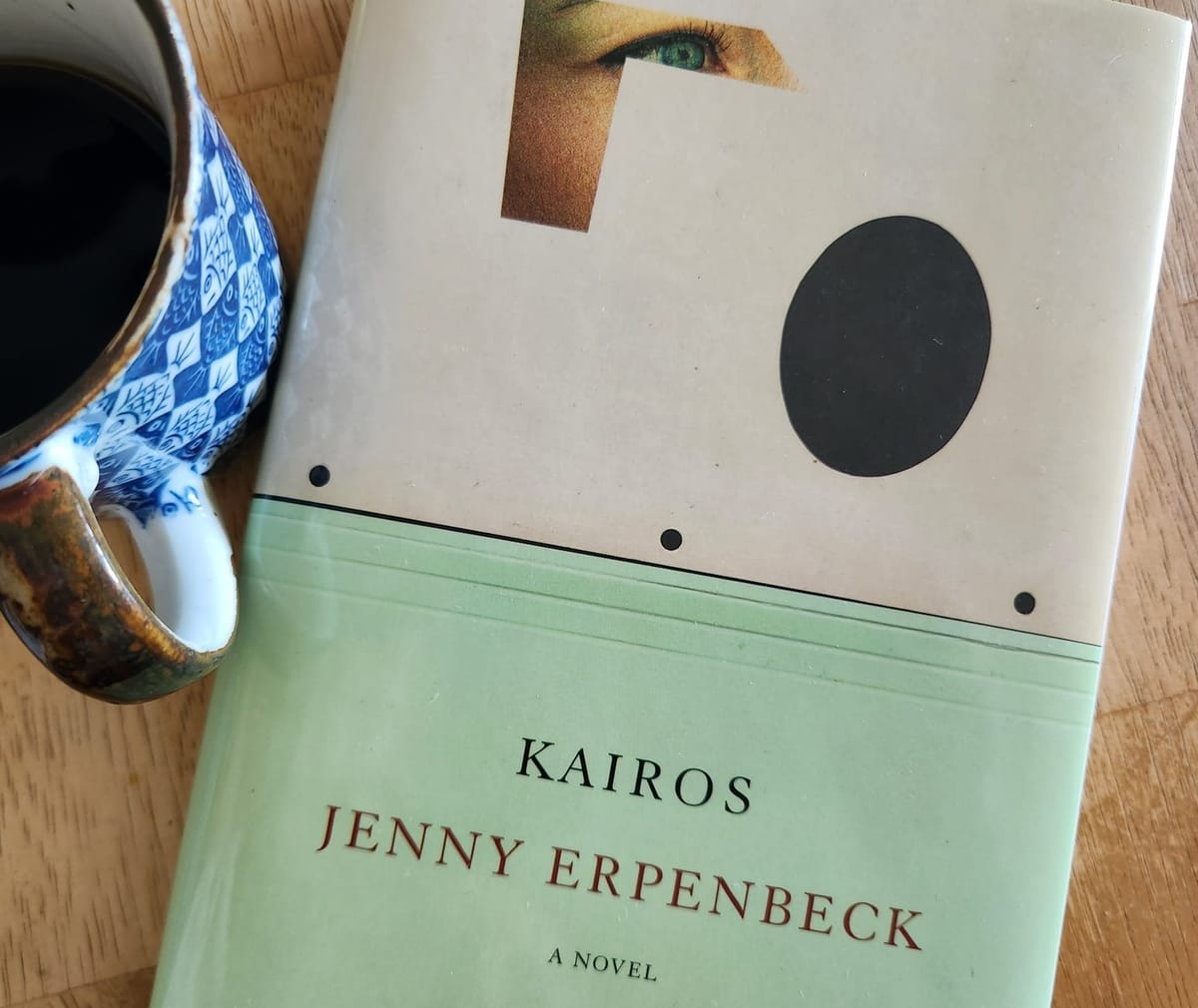

- Kairos: Jenny Erpenbeck’s brutal novel about personal and public politics

- The Critics at Large explain why we need critics to face the crush of culture

Kairos: Jenny Erpenbeck’s brutal novel about personal and public politics

We’re nearly halfway through the year, and the best book I’ve read in 2024 is the first book I read: Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos. I read it slowly over the second week of the Christmas holiday. When my kids were swirling around me, I worked my way through Erpenbeck’s East Berlin, fretting over the central relationship and grappling with the philosophy of private and public political life. The book worked as a distraction amidst the chaos of a holiday with young kids. It was a world into which I fell easily and which overwhelmed me.

Following the young Katharina through her relationship with the much older Hans, Kairos is a story of an all encompassing romance, one that takes over, teeters on the dangerous, and blocks out the rest of the world. The rest of the world in this case is the lead up to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Katharina is obsessed with Hans, ignoring the revolutionary zeal of her peers, while Hans tries to control everything, haunted by the decline of a lifestyle in which he thrived.

The epigraph to the first large section of the book reads,

Nothing exists but you and I

And if we two be not

Then god is no more god

And down must fall the sky

-Angelus Silesius

This quote from the 17th century German religious poet sets the reader up for the relationship they’re about to dive into. It is everything. The stakes are as high as the heavens. Katharina and Hans’s focus on each other pushes them, Hans in particular, to do terrible things. The power dynamic and the abuse are uncomfortable and deeply relatable to someone such as myself who was once young, lost, romantic, and more emotionally vulnerable than I knew.

I was once Katharina. Making poor choices, getting myself into dangerous relationships, and working against myself–that was my early twenties, and it was painful to read, in a good way, like a big blubbery cry. Katharina’s choices are at once unbelievable and familiar, similar to the way so many women operate within abusive relationships. The impulse to justify is strong, especially when the model of love in so many canonical romances is one that is “intoxicating.” That justification is a tearing down of self confidence. Katharina sits at her little table in her apartment listening to tapes of Hans berating her, internalising his vitriol, and enduring a punishment she does not deserve, however much she believes she does. It’s not an easy behaviour to see in myself, but looking at a character do the stupid things I did was brutally cathartic.

Coming out the other end of a very emotional reading experience, I learned more about what I love in a book. That private/public dynamic, where the private seems to eclipse major historical events, holds a truth that I’ve only encountered in novels. I am certainly no great consumer of music or theatre, but I can think of a number of books, like Kairos, that are set against history and give value to regular people: Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, Chiminanda Ngozi Adiche’s Half a Yellow Sun, anything by Magda Szabo. I’ve been reading this way for at least a decade, but it took Kairos hitting me over the head to realise it.

Read Kairos if you love any of the historical dramas listed above, but also if you value brilliantly brutal prose. Erpenbeck is fierce in the way she faces abuse in the home and abuse in the public state. She challenges readers to hold those two spheres as equally important.

“The Case for Criticism”: The podcast that started it all

Critics at Large of The New Yorker released their episode “The Case for Criticism” in January, and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. It inspired me to share my thoughts on the stacks of books I read and to do it because the world needs criticism from humans. AI is wringing the creative industry for all its worth, and if we don’t insist on the value of the human voice, will that value persist? Will our creativity diminish?

Event notice: Confabulation

I’m performing at La Sala Rossa with Confabulation on May 17th at 8pm. Come hear me tell a story about miscommunication at Confabulation’s 15 year anniversary show.