Books, help me see Palestine

On reading to see

Lately, I’ve been reading about Palestine. At first I thought I was doing it to understand what has been happening in Gaza and the West Bank, but I realize now I am reading to see. To understand means to make sense of. That means there is some sense to make. But is there sense in the genocide of Palestinians? No. And so I try to at least see.

We hear a lot of talk about peace deals and international negotiations—oligarchs, mediators, third party whatevers gather to "solve" the conflict. But what is actually happening to the people who are there? How do they see Palestine? The history is long and perspectives contradict. So how am I to approach it as an outside learner?

Typically, the way I learn the world is through fiction first. Fiction gives me an intimate view. Non-fiction reading supports it. Both are necessary but I start with fiction.

On The Book of Disappearance and Ibtisam Azem

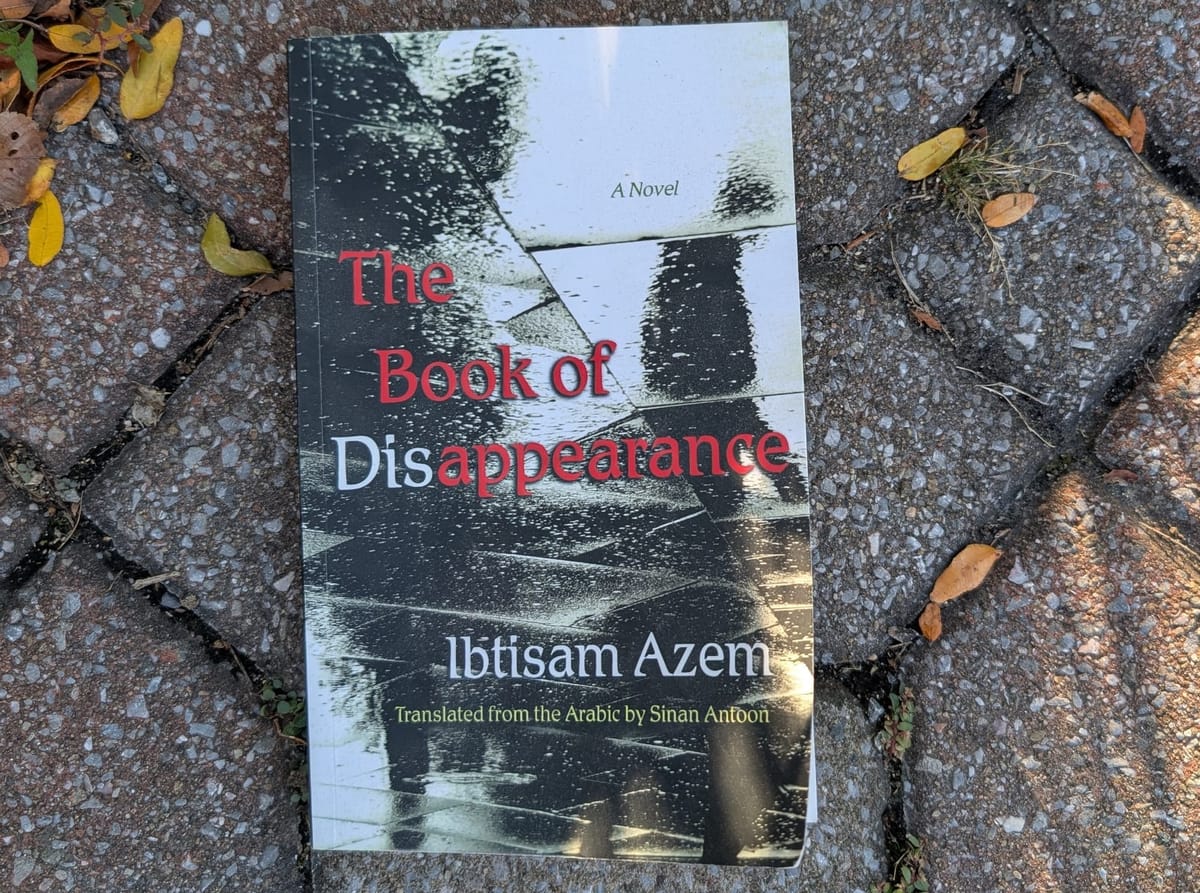

In this issue of Billy, I want to share a book that is helping me see Palestine: The Book of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem. The version I read was translated from Arabic by Sinan Antoon.

Born in Taybeh, a village in the West Bank, Ibtisam Azem grew up near Jerusalem. Her mother and grandmother were displaced in 1948, during the Nakba. In Arabic, Nakba means “the catastrophe.” People use it to refer to the mass displacement of Palestinians in 1948, and it is the central historic catalyst for the plot of The Book of Disappearance. It is one of those historical moments represented in dramatically different ways depending on where it is taught.

In an interview for the Booker Prize website, Azem describes the way her history was twisted in school,

“In our Hebrew literature classes, we had to read Zionist literature which spoke of our homeland as empty land. This was antithetical to the oral memory and history I heard at home from my mother’s family who were internally displaced from Jaffa during the Nakba.”

There are layers to Azem’s personal history book, layers of perspective and interpretation. When she speaks of the stories she was told of her homeland, she speaks of intentional interpretation of history to suit the narrative of those in power. That’s a danger we are all too familiar with, and one captured deftly in The Book of Disappearance.

To be internally displaced

The provocation of The Book of Disappearance appears in the first sentence of the blurb on the back of the book, “What if all the Palestinians in Israel simply disappeared one day?” So, in one sense, it is speculative fiction. But much of the book exists in the memory of the two narrators: Alaa, whose journal addresses his Palestinian grandmother who was displaced in 1948, and Ariel, a notable liberal Israeli journalist and friend of Alaa. In the novel’s present, all the Palestinians in Israel have disappeared without a trace. The country slowly notices and reacts, while Alaa searches for his friend and writes political and cultural criticism in his column. He finds Alaa's journal addressed to the displaced grandmother and learns a history that is distinctly personal and intimate.

Deeply immersed in Alaa’s memories, Ariel asks,

“Does a place have memory? What if we were to place a person who knew nothing of the place’s history, not even its name or geographical location. If we were to take him, and have him walk in the city or place, would he feel the place’s memory? Which memory?”

This is a really good question. If, instead of reading to see a place, I could go there and feel it with no preconceived notions, what would I see in Palestine? If I only encountered it with my senses, what would I learn? How would my sense of the place change if I visited twice, once before 2023 and once after the eradication? I would see people.

The Book of Disappearance is constructed of the journal entries of Alaa, and the columns of Ariel. They each have a history, a perspective. They each create something of their experience in writing. And that’s how I am able to see Palestine, only through their lens, which is filtered through Azem’s. The truth is, we see places through a prism of perspectives. What I love about fiction is that it acknowledges the prism. The Book of Disappearance is about the prism.

When I look at Palestine these days, I see people who want to live their lives. I see a state crushing lives, making them impossible, or snuffing them out entirely. I see erasure. Erasing perspectives is dangerous for all of us. If we submit to one story and follow along blindly, we are complicit. Even as "ceasefires" are enacted in Palestine, journalists are still not allowed in. We are in danger of submitting to a single story. As a first step, I encourage you to read The Book of Disappearance. Then read more Palestinian literature. Turn the prism over in your hand a few times, and then guard it.

I leave you with these words from Palestinian writer Omar Hamad,

"Perhaps I will write—not to immortalize the pain, but to say that we were here… loving, dreaming, planting, drawing, singing, reading, writing… before our lives were reduced to a passing news bulletin or a cold political statement. And I will keep writing, until the last drop of ink… or blood."

-"Omar Hamad in Gaza: 'I once wrote ith ink, today I write with ashes."

Podcast recommendation

Ezra Klein “When is it Genocide” with Phillip Sands

For a discussion of the legal definition and history of genocide and some analysis of whether or not what is happening in Palestine is genocide, listen to Ezra Klein’s interview with Phillip Sands. Note this was before the recent UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory finding that Israel has committed genocide on the Palestinian people.

Note: No large language models were used in the making of this article. My em dashes are my own.